During Anime Expo 2024, I (along with a handful of journalists from different publications) had the wonderful opportunity to interview Gensho Yasuda before his Make A Girl film debut. A rising figure in the world of CG animating, Yasuda-san is best known for the short clips he would release on SNS sites like YouTube Shorts or X (formerly Twitter); often themed around a particular character archetype, like “ninja girls” or practicing a specific design as like fox nekomimi. One of these shorts, titled Make Love, would become the basis for the upcoming full-length film Make A Girl, produced by the newly established Gensho Yasuda Studio. Though the much-anticipated work is set to debut in Japanese theaters on January 31st, 2025, the lovely people at KADOKAWA invited us to a surprise premiere exclusively at the illustrious TCL Chinese Theater in L.A– a day before its official premiere at the 37th Tokyo International Film Festival!

As previously mentioned, the genesis of this film started with the release of the short animation Make Love in 2020; introducing us to the story of genius inventor Akira, his creation of a girlfriend, and questioning if artificial programming can result in organic feelings all in a little over 2 minutes. The animation received a lot of attention and praise online and would go on to win a prize at Japan’s oldest CG animation contest later that same year. The popularity of Yasuda-san’s works– and skillset– grew visibly over the next 4 years, culminating in a following count of over 6 million across his various social media accounts. As these well-deserved achievements continued to rack up, the development of his breakout short animation evolved into the development of a full-scale major film project! Yasuda-san’s usage of free tools with a low barrier to entry like Blender has long been acknowledged, but the creation of Gensho Yasuda Studios authored the newest chapter in his artistic journey. As he mentioned in our interview, working in a team for the development of Make A Girl was a very different experience than when he created the framework animation Make Love years prior. As he put it, “When producing in a team, I think strength in numbers is the greatest weapon… Each person, each team member, has different skills and expresses them in different ways. So, accumulating ideas in the team for Make-A-Girl was a big discovery and a first time for me.”

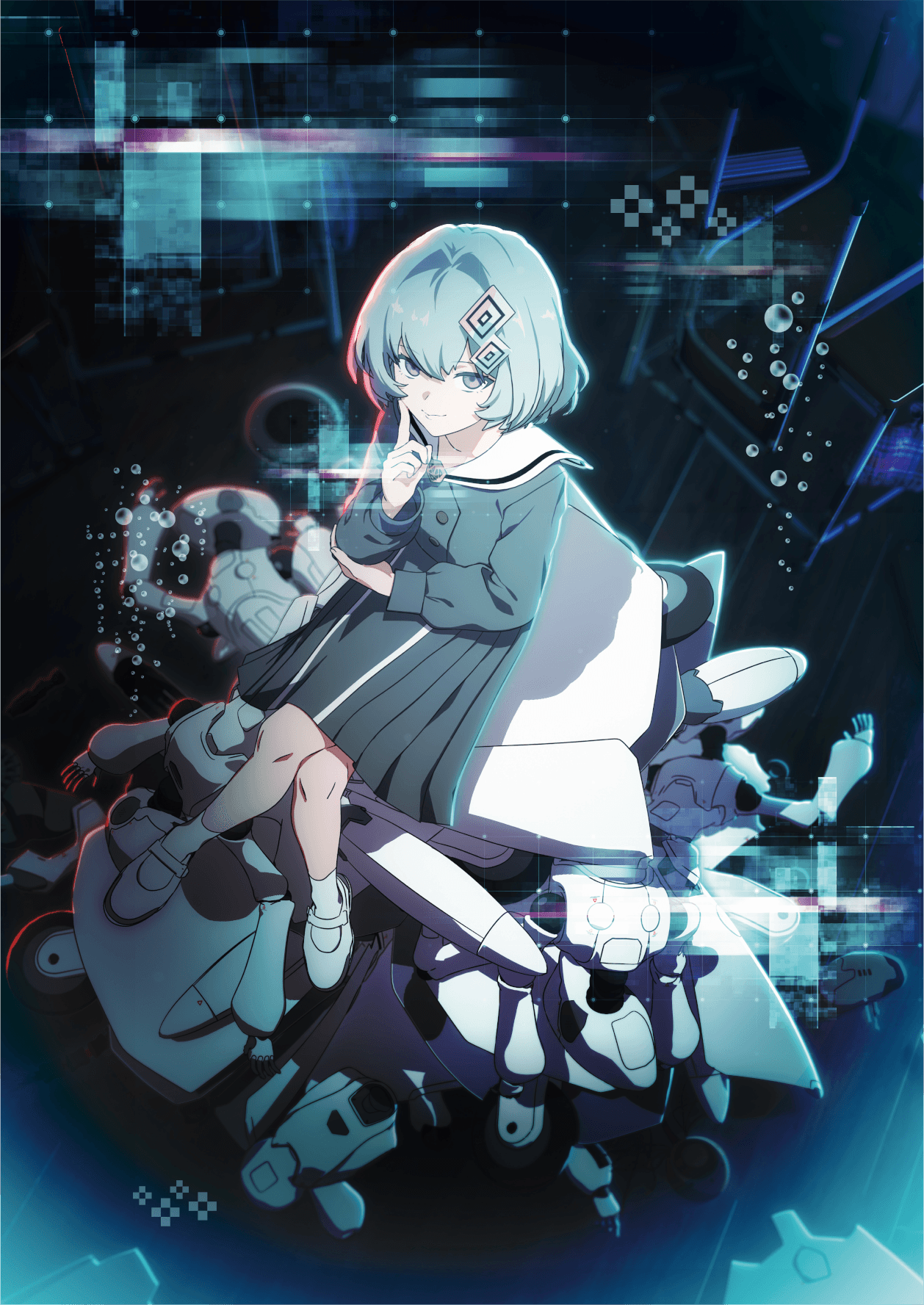

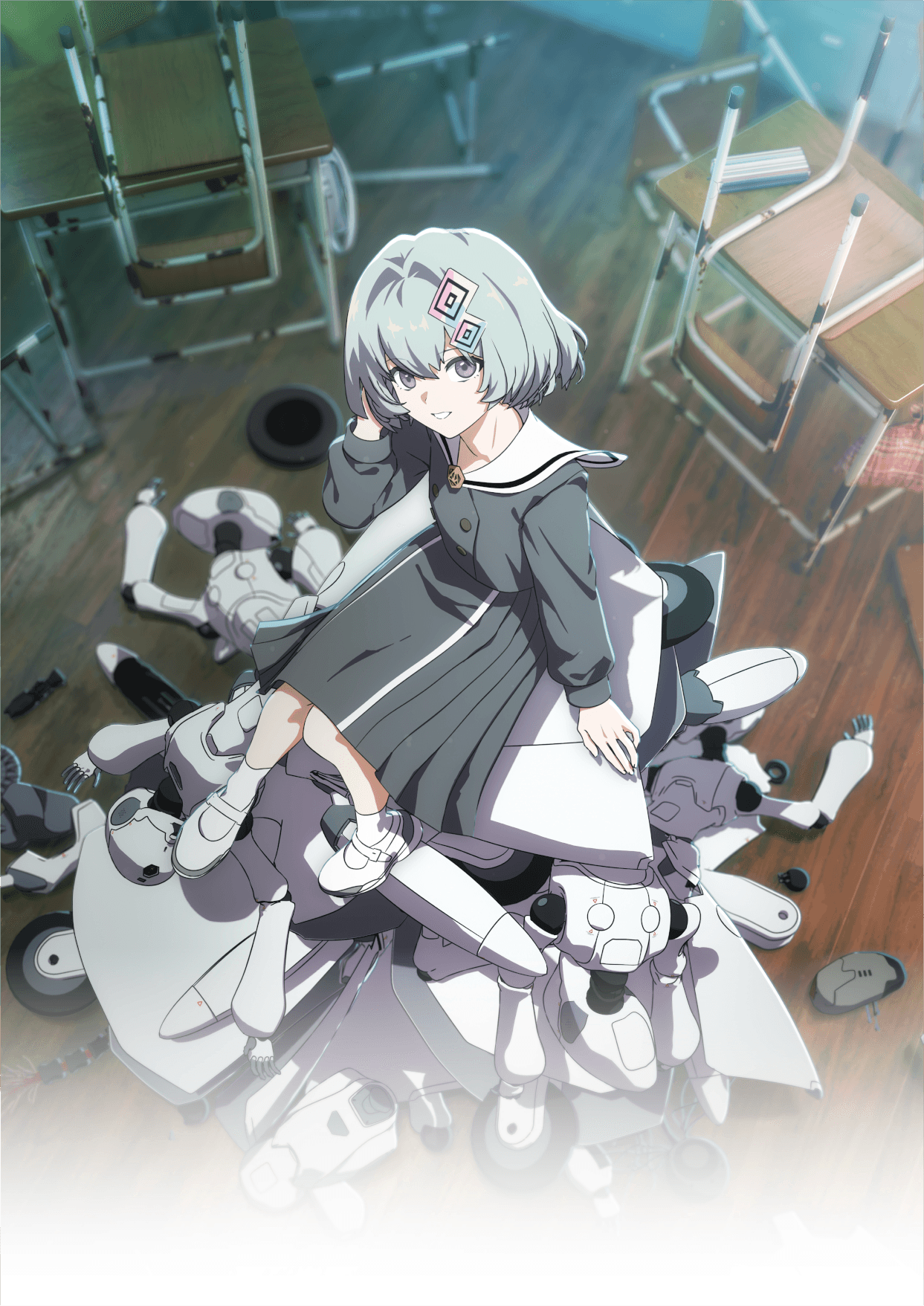

This culmination of skill and ideology mixing can be seen in the immediate quality upgrade shown in the full-length production of Make A Girl. Those who followed the work’s development can spot the building blocks laid by the initial short animation, such as initial character designs. Our main character Akira’s design and motivations remained mostly unchanged outside of some more eccentric steampunk-esque styling, whereas No. Zero underwent more of a design change. Even something as seemingly inconsequential as changing her original shoulder-length green hair to a choppy silver bob changes her overall impression. There were also, of course, some animation style changes; a visible skill upgrade, and evidence of other artists’ contributions. Running and motion animations for the 3DCG models were much smoother than before and well done for the scale of the project. I was also looking forward to the performances by the voice actors (Yasuda-san’s short animations never featured voice actors so this would be a new element for his animation), and how that would change or deepen a character’s impression. The cast was filled with some stacked talent like Atsumi Tanezaki (Anya from Spy x Family). Yasuda-san spoke highly about the voice cast, “[the voice actors] breath[ed] life” into the characters in a way that allowed the audience to connect with them more than they had before.”

©Gensho Yasuda/MAKE A GIRL PROJECT

Another change I found interesting was the title change. I’m sure there are various reasons behind the production’s changes, but it felt like the original title of Make Love was more fitting for the story the author was trying to tell. The main conflict between the main characters, after all, is the argument of whether man-made feelings can be real. Akira, who programmed No. Zero to be his girlfriend despite his lack of knowledge or experience of interpersonal relationships, is hardly an authority on human emotion. On the other hand, the translation options of kanojō as it relates to the title is also interesting. Did Akira create a girl (kanojō) or a girlfriend (kanojō)? I think the answer was made clear by the end of the film, especially considering the development both characters experienced throughout the movie.

©Gensho Yasuda/MAKE A GIRL PROJECT

“Guy is stuck in a rut, hears from a friend that having a girlfriend can help you ‘level up,’ so Guy creates an (artificial) girlfriend” is the kind of premise I would usually skip out on. Moral ambiguity aside, the trope-y nature of such a plotline doesn’t tend to interest me. But there were a few reasons why I found Make A Girl interesting (some of them I will be doing my best to keep as spoiler-free as possible!). One of these things I liked about the movie was something Yasuda-san prefaced himself regarding plot continuity and development in his works. As he remarked in the interview, “So, for me, when characters go through hardship and they experience an injury on their body, like a scar that won't go away or some sort of condition that won't go away, I think it's important not to just make that injury or illness go away and create a happy ending but shows characters that are strong enough to go on despite that injury.”

Where human nature dictates we as the audience revolt at the idea of characters we’ve grown to care about experiencing “true” harm, it’s that same experience that makes characters feel more human. It’s more satisfying that the trauma the audience witnessed is not retconned and has some meaning, like having a narrative payoff. The climax of the movie was emotionally cathartic to both the character and myself– though I suspect I as the audience member shouldn’t have been as approving of the dire straits one of our main characters finds himself in.

©Gensho Yasuda/MAKE A GIRL PROJECT

Unfortunately, our main character Akira is not one of the elements of this film that I enjoyed, simply because of how uncompelling I found him as a protagonist. His path to understanding and respecting No. Zero as her own person– much less her feelings– was confusing to me, and the openness of the ending didn’t help with the ambivalent ambiguity I felt towards their relationship. I was also surprised by the missed opportunity of fleshing out the possible conflict with– I presume– the second female lead Akane, who very clearly had feelings for Akira despite his apparent obliviousness. At one point in the film, it seemed like we might explore this plotline, but it seemed to just dissolve. This, plus the slightly underwhelming antagonist “mask off” reveal and explanation, made me wonder if there might have been more planned for the movie, or perhaps a sequel in the works. Besides Akira and No. Zero’s relationship, the development of the other story elements took a backseat when neither of the two weren’t directly involved. I was interested in seeing more of the antagonist’s progression, after observing a few “breadcrumb” moments of their storyline forming, and hope that we can get some bonus content for them.

At the end of the film, there was a short Q&A session for the audience, where the audience was encouraged to ask the PR representative some questions. Since the Q&A rep wasn’t personally familiar with the intimate production details of the film, the questions trended toward broader industry-related inquiries. One such discussion topic was how tools like Blender are creating an opening in the industry not just for more indie talent like Gensho Yasuda but also creating an entry point for foreigners interested in the Japanese animation industry. In our interview Yasuda-san agreed with my observation that 3DCG animation isn’t regarded too highly among anime fans, saying “There's a clear reason why 3D hasn't really been holding up to the 2D anime, which I think is just the experience, and the know-how isn't deep enough yet in the industry.” As mentioned at the Q&A session, those working in the industry now are seeing that as 3D animating becomes a more sought-after skill set, studios are outsourcing talent internationally to help deepen their development and know-how of CG animation. The release of Make A Girl is a significant marker of the growing popularity of the 3DCG medium, and I’m excited to see if it will inspire a new generation of artists to enter the industry.

When Make A Girl finally makes its worldwide debut, you should definitely go and see it for yourself. Considering the themes of the film, it seems like the type of work will have slightly different interpretations depending on the viewer. How you feel about A.I, the concept of love, and the meaning of humanity will shape your view of the movie overall and how you respond to the film’s quiet assertion that to love is to be human.