Alright, quick show of hands from the girlies: How many of us can relate to the shared experience of getting into the world of anime and manga and being told, “Why don’t you just watch a Shōjo?” It’s a (infuriatingly) common experience shared among femme anime fans, receiving this lukewarm NPC-loaded criticism from anime dudebros for the heinous crime of your girlish presence in “their” fandom. Rarely a sincere question, it’s usually an exasperated and defensive reaction to “uncharitable interpretations” in discussions of popular Shōnen shows.

Shōjo, at its core, is a genre of media (anime or manga) aimed towards a female audience, while Shōnen is targeted towards a male audience; so obviously, girls should watch anime for girls, right? Well, we could have an entirely different discussion about the overall respect of Shōjo as a genre, but I have a different—and equally contentious—topic to discuss. Why are the girls (including me) obsessed with Gojo, and why are the dudebros so pissed about it? Or, more eloquently put, how can we understand sexualization and desire through the female gaze in the context of anime and fandom?

The Female Gaze in Fandom

Anime fandom for femmes looks vastly different than that for male fans. From fan works to discourse, there is an observable difference between the frames male and non-male fans use to participate in—and enjoy anime. And with big recent anime titles being more universally enjoyed by both audiences, the male fandom seems to be growing increasingly aware of that fact.

One of the biggest complaints towards the female fandom side has always been the contentious topic of “shipping” within Shōnen titles; however, now the sexualization and desire aspect is becoming more relevant. Now, it’s not just the dudebros rubbing their hands together like delighted flies at suggestively positioned fanservice angles; the girls are getting them, too. (Thank you for your service, MAPPA animators!) Fanservice doesn’t necessarily have to be sexual; it simply refers to any extra material added “for the perceived or actual purpose of appealing to the audience.” But as a trope, it’s mostly included as a cheap way to get the fanbase fanning their faces and pulling at their collars—usually targeted towards the horny male fans. In recent months though, there’s been an increase in horny fanservice for girls; and let me tell you from personal experience, we’re eating it up!

The reaction to fem-presenting anime fans loudly and lightheartedly discussing their attraction to popular male characters is rankling some feathers, though, with male anime fans growing more and more irritated by it, even though this “annoying simping” doesn’t even rank against some of the behavior and jokes they have been making about female characters for years. More than just simple banter and jokes on X (formally known as Twitter), I think the implications of female desire increasingly becoming relevant in anime is an interesting topic that gives insight into different fandom experiences. Even more interestingly, it seems the creators in charge of these anime have keyed into this rising element of female desire and are leaning into it through their portrayals and framing of characters. This has led me to wonder how the female gaze applies to anime, how fans can view anime through it, and how modern anime studios are increasingly catering to it.

Understanding the Female Gaze

Before we discuss the use of the female gaze as a framing, though, we must discuss what the “female gaze” refers to. As a feminist theory, the female gaze centers the woman—her desires, agency, projection, and consumption—and how it influences perceptions or portrayals of sexuality and power. The same reason shirtless flexing gym pics get less swipes than a relaxed shirt-on picture is the same reason characters such as Cowboy Bepop’s Spike, The Way of the Househusband’s Testsu, and Demon Slayer’s Tengen are so popular with femmes. The entire debate of “what women really want” exemplifies why men rarely understand the female gaze; it’s the misunderstanding—or rejection—of feminine desire as its own force, instead of just something passive to be enjoyed by men.

Returning to Shōjo, this female-focused gaze appeals to many of its enjoyers. As Nathan Winters puts it, “Even though female characters are portrayed as passive at times, and support the male dominated ideology of the culture, the male characters are even more sexualized, exposed, and voyeuristically shown to the female readers” (Sexual Violence Against Women in Shoujo Manga, p.27). Well, that should be obvious, right? Shōjo is for a female audience, after all, so of course, it would be catering to the female gaze. But then I ask: if Shōjo is meant to appeal to the female gaze, what is the common shared element with Shōnen that also draws in a femme fanbase despite not being written for their gaze? Is it the romance and personalities? The fanservice-y tropes? The hot male characters strutting around? Well, I think it’s all that and more.

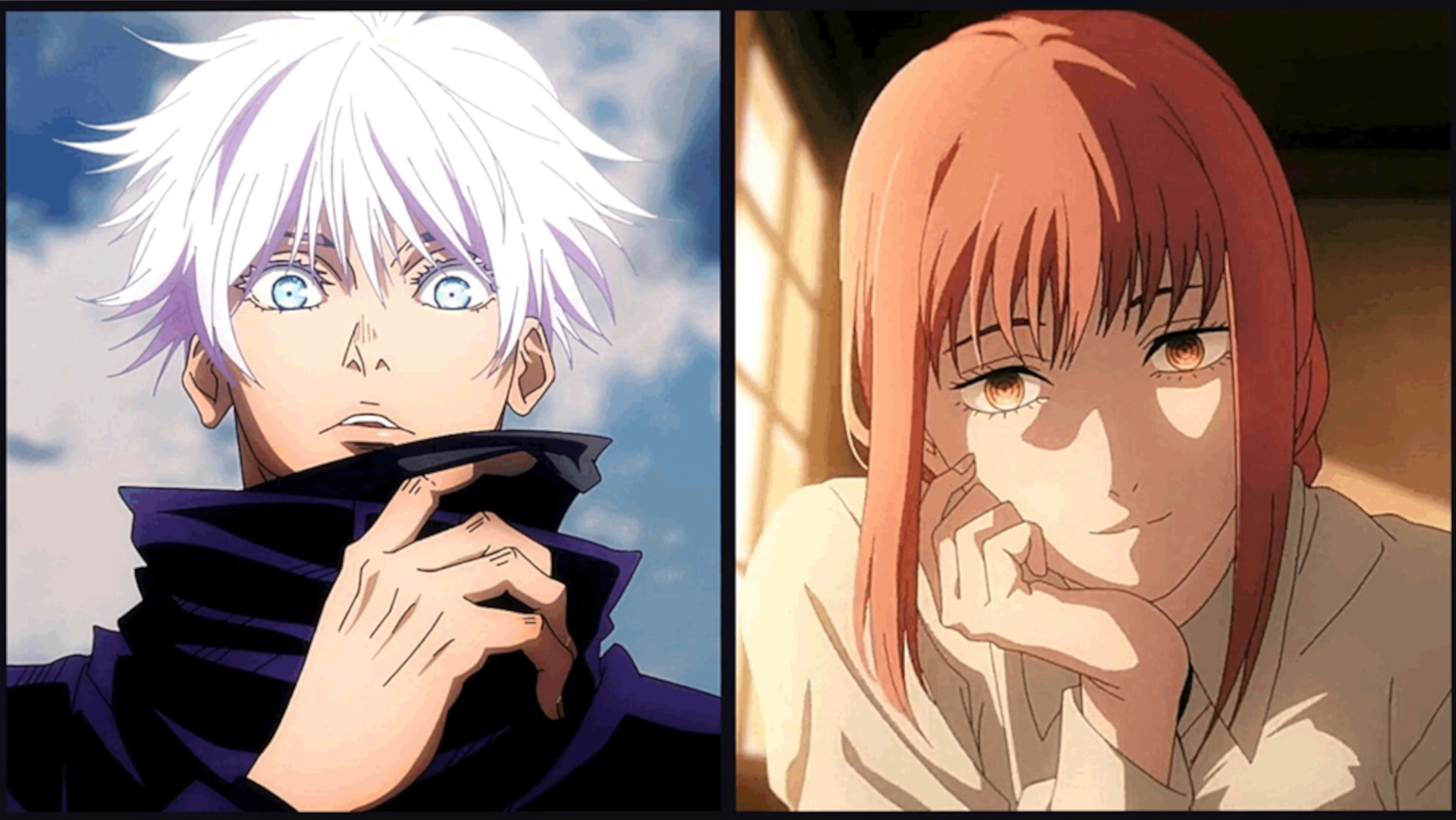

Let’s look at two of the most popular characters of modern anime in the last few years, as an example: Makima (Chainsaw Man) and Gojo (Jujutsu Kaisen). Both works debuted in Weekly Jump in 2018, were produced by the same studio (MAPPA), and share similar themes. They were two of the most celebrated and popular titles to come out of modern anime in the last three years, with those two characters rising to the top as some of the most talked about. Still, I do want to compare how the differently gendered—and sexualized—gazes each were written through affect their perception in the diverse fandom of modern anime.

Both Gojo and Makima fill a similar character trope in their respective stories, one that is usually present in Shōnen-leaning works, that being the cunning, confident, always two steps ahead “OP” teacher or mentor role. This role places them firmly next to the protagonist, their own power and dexterity a foil to the underdeveloped and amateur mentee they take under their wing. Yet Makima is clearly written through the male gaze, appealing greatly to the male fanbase at large. While Gojo, interestingly, seems to have initially been written through the male gaze, but increasingly shifted to a more female-oriented gaze as time passed. Both gazes are more clearly demonstrated through the anime adaptation, which I think is just as important as the source manga.

In Makima’s case, her male gaze alignment might be a little harder to pin than her other counterparts. The “OP” character archetype she fits into, after all, seems to contradict some of the most common “vulnerability” and “weakness” aspects often woven into other male desire-centered characters. Despite this, though, there are clear indications of the gendered gaze she was constructed through. The female gaze is not just confined to a voyeuristic role; it is also instrumental in constructing a masculine identity. As writer Kevin Goddard puts it, “men’s identities are inextricably linked to their understanding of what it is that women expect of them” (Looks Maketh the Man, pg. 34).

For Denji, he is an inexperienced, severely neglected, and vulnerable teen boy; his initial motivations are sexual and intimacy-based. Makima, an older female in a position of power over him, helps him further develop his character as a young man. In the words of Goddard, “Since [Rabbit’s] masculinity is affirmed only by a female accepting his image of her and hence of himself, it is one of well-nigh complete dependence. He has little or no means to genuine knowledge of women and is afraid of attempting any non-stereotypical knowledge because it will mean a redefinition of himself” (Looks Maketh the Man, pg. 33). Fujimoto also revealed an intentional play on her name in that removing the “ki” you’re left with “Mama,” in connection with Denji, who has always been pursuing maternal affection. This ties in with one of Makima’s later revealed hidden desires: yearning for a family and a happy life. A secret desire to have a family is a commonly included trait in male gaze-centered female characters, this “natural” desire contrasting with her other traits that are supposedly contrary to the idealized women. Yet, these traits are highly sexualized and feminized regardless. For all of Makima’s power and “girlbossery,” her (manipulative) mix of maternity and weaponized Freudian sexuality reveals a female character that was fundamentally catered to a male audience.

Gojo, on the other hand, is interesting because he is written in the stereotypical “OP” mentor or teacher role in every action based Shōnen. Due to this role’s very nature, he was initially penned for a male audience. This is evident in his self-assured and confident demeanor, interpersonal ease, and grasp of command. Male characters through the male gaze are idealized for projection, and that means the traits highlighted are the ones that men feel are most important for other men to have. Things like arrogant confidence, unapologetic power, and an unflappable rejection of being “emotional” are commonly seen and, in fact, were integral parts of Gojo’s design. It became increasingly evident through airing, though, that the main audience this character appealed to was not the male Shōnen crowd but—overwhelmingly—the femme one. What do you do when faced with an unexpected but incredibly passionate audience? You quickly cater to them, of course!

While the fundamental idealized masculine traits making up Gojo are at odds with the female gaze, Gege and MAPPA successfully transitioned Gojo into a female gaze-centered character so well it’s become a common joke that Gojo was “born to Shōjo, forced to Shōnen.” This shift occurs internally and physically; the subtle cosmetic details and changes to his design drew the girlies in, and the development of those initial traits into something meaningful made them stay. His confidence in his power is not selfish; it’s protective towards those he cares about. Where vulnerability was initially traded for a lackadaisical and jokey attitude (even admonishing a female character for being “too emotional” because “men don’t like that”... sigh), emotional expression bloomed in Gojo’s character. We saw his anger, his fear, his despair—even his love, and the irreplaceable loss it left (argue with a wall, I saw the “Hidden Inventory” arc with my own eyes). The audience also saw how all of those emotions built his strength. In a similar way to Makima’s (and other femme fatale types) secret desires of being soft and familial appealing to men, the dichotomy between masculine strength and expressed emotion is often what appeals to female desires. It softens the edges of macho arrogance to calm confidence, overwhelming power feeling more like safety rather than sinister. And that’s to say nothing about his actual design; I just know MAPPA had the same pens that worked on Victor Nikiforov lovingly sketching Gojo out, too.

For the Fans

As mentioned earlier, fanservice in anime is not at all a new concept and is abundantly present in most anime to some capacity. Designed to appeal to the audience’s gaze, these “unnecessary” scenes often objectify the fandom-wide sexualized character for no other reason than what Laura Mulvey, creator of the term “female gaze” called scopophilia, “pleasure in using another person as an object of sexual stimulation through sight.” Archie Fenn further explains in an article about the male gaze in My Dress Up Darling that the invisible man behind the camera figuratively “dismember[s] their attractive body parts in a way that reduces their personhood; think about fanservice that focuses on a girl’s boobs, butt, or crotch much more than her face.” The main demographic representing the anime fandom for a long time was cishet male fans, so this sexualized objectification was mostly aimed toward female characters (with some notable exceptions: I’m looking at you, Iwatobi Swim Club…). But with the popularity of such a breakout new-gen top character, paired with a rising standard of animation, that has begun shifting more, too, with a major nod to the trend going to Gojo.

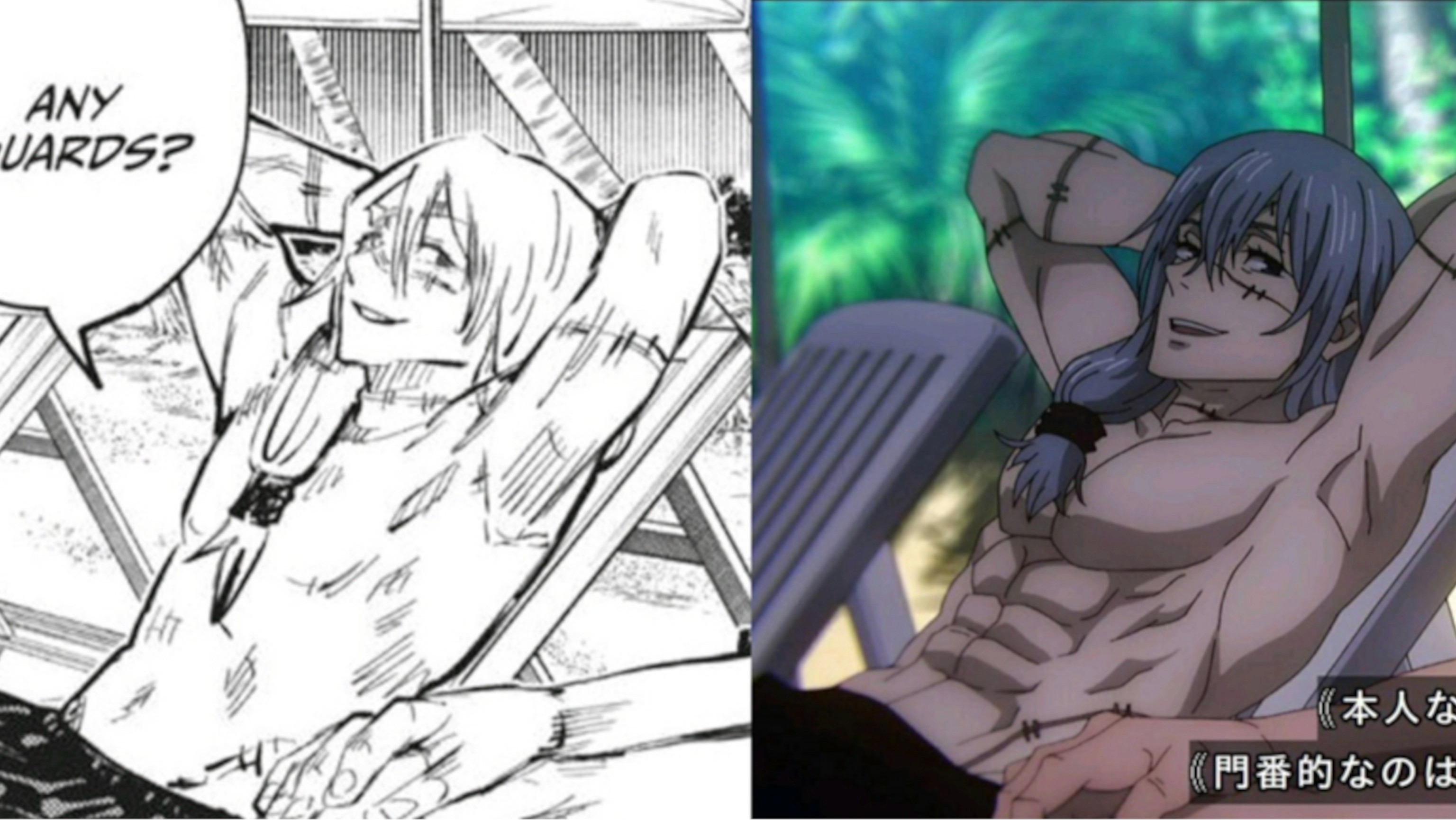

The female voyeuristic gaze’s evidence was clear in such plot-relevant scenes as “intimately animated hand holding (™), peachy tinted lip balm glaze (™), mechanical bull riding pose angle (™),” and more. And this has spilled over into other male characters like Nanami (even besides that scene, he’s always been for the girlies), Choso (anime original panels of full frontal abs), and Toji (his…entire character, really). Notably, though, this has not spilled over to female characters like Nobara, Maki, or others, despite their high popularity within fandom as well. These female characters are also written with a more female-oriented gaze; their strength and vulnerability are much more complex and human than other “girlboss” characters designed for a male audience. With all of the characters, regardless of gender, their “Shōnen heavy” traits of power are still highlighted without compromising or contradicting their unique vulnerabilities and emotions. The female gaze is not just applicable to Shōnen, though; various genres like Josei (marketed to adult women) and Seinen (marketed to adult men) that explore more complex story themes can also be viewed similarly through this lens. I would highly caution you, though, dear reader, against diminishing these gendered gazes as a strictly cis-heterosexual experience; queer and femme anime fans’ experience of the male and female gazes in Yuri (lesbian) and BL (gay) works can differ quite a bit.

As anime continues to reach new peaks and diversify, so will its fandom. As the femme fandom grows and is more represented, female desire and the female gaze will become more prevalent even in anime with a high percentage of male fans, like Shōnen. A represented female audience base means a represented consumer base, after all. Big-breasted anime girl figurines are no longer the only degenerate merchandise available for fans (we’ve all seen the NSFW Gojo figurine, right?). We’ll continue to see femme fan-oriented characters like Loid Forger and Gojo, and we’ll continue to see the vocalness of the femme fandom in anime spaces. While it will likely continue to irritate self-aggrandizing male fans who cringe at the implication that they are no longer the only demographic being catered to, I think female anime fans will increasingly influence conversations in both anime and fandom. Or, in other words, let women enjoy things!