Making A Black Character - What Makes A Good Black Character in Anime?

Aali Brown-Malika

Mar 7, 2024

“As anime continues to reach new peaks and diversify, so will its fandom.” This statement was the base of my previous argument in defense of “the girls,” and the growing influence of the fem-presenting fandom on the anime industry as a whole. However, there is another demographic this statement can apply to, that being Black fans in anime. Similarly to the female gaze influencing the way characters are designed, the growing awareness of multicultural consumers – as well as cultural sensitivity – also has an effect on how characters are both developed and received. Also similarly, there has been a long and problematic history regarding the way these characters were portrayed in anime, as well as villainizing or downplaying the feelings of fans belonging to that group by the wider (whiter) fandom at large. As a Black fem, imagine how tired we are!

Most manga and anime are created by Japanese artists first and foremost for a Japanese audience; that is well understood. Thus, most cultural and societal depictions are being written through a Japanese centered viewpoint. This on its own is understandable; however, the overall isolationist “homogeneous” argument has been used as a shield to combat criticisms of troubling or insensitive elements for many years within the anime fandom. And yet the “cultural ignorance” argument is only applied to problematic portrayals of BIPOC foreign characters. Contrary to White/European characters, Black characters are often not well developed, drawn, or voiced, especially for comedic effect. And while there have been considerable improvements over the years, I think the best way for Black characters to progress in anime would be for there to be a clear understanding of what makes a good Black character.

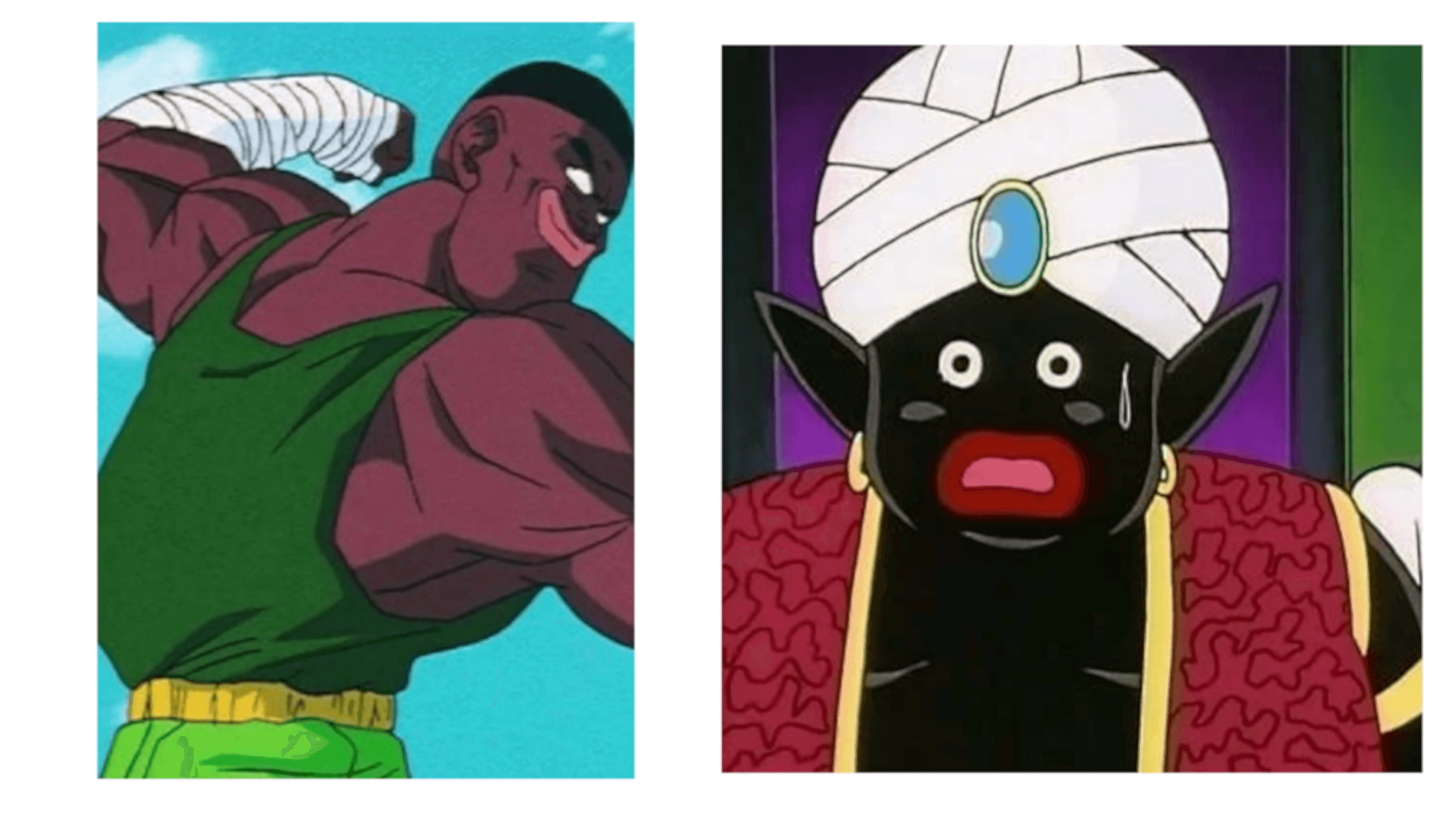

It’s easy to see why characters like Mr. Popo (Dragonball) would draw backlash, but it wasn’t always such a matter of course. The minstrel-like design of black-skinned characters outside of the Western world has long been contentious, due to the lack of ubiquitous knowledge of anti-black elements that are centered on specifically the African-American experience. “They aren’t supposed to be black” as an excuse feels like paltry lip-service; why are these exaggerated features and tar black skin necessary to highlight concepts of “exotic” or “foreign”? Declaring the standard, the “normal” in anime as whiteness inherently others differing features in a hierarchical way. That’s why depictions of black characters in shows like Cowboy Bebop were so important. As director Shinichirō Watanabe put it, “Lots of times when you watch anime, the characters have white skin — all the characters in fantasy stories all have white skin, which I never liked. I wanted to have lots of characters in Bebop without the white skin, and if people weren't used to that, well, maybe it would even make them think a little bit about it.”

In today’s era, anime is appealing to a much wider audience internationally; and with that, there comes more responsibility on mangakas (manga authors) and studios in not alienating the minority populations (like BIPOC and queer fans) that are also prevalent in the fandom. In my own experience, there have been many aspects of Black characters in anime that have rubbed me the wrong way over the years. I have also seen shifts in the way these characters are presented, and I think it’s worth discussing what exactly would make a “good” Black character. Just as Black people in the real world are diverse and multifaceted, so should the anime characters depicting them.

Design, voice, and personality; these are the subcategories that must be considered when creating any character.

Think of the most side-eye worthy Black character you’ve seen in anime; what was it about them that was so off putting? Personally, I always jump a little in my seat when the camera pans to introduce a Black character and the first thing we see are peach pink sausage lips. Followed by a deep sigh at the oafish, “broken” speech they use. If we’re lucky, they’ll be relegated to one off “comedic” relief; if not, they’ll be rude and slovenly for no other purpose than to antagonize or fire up the protagonist(s).

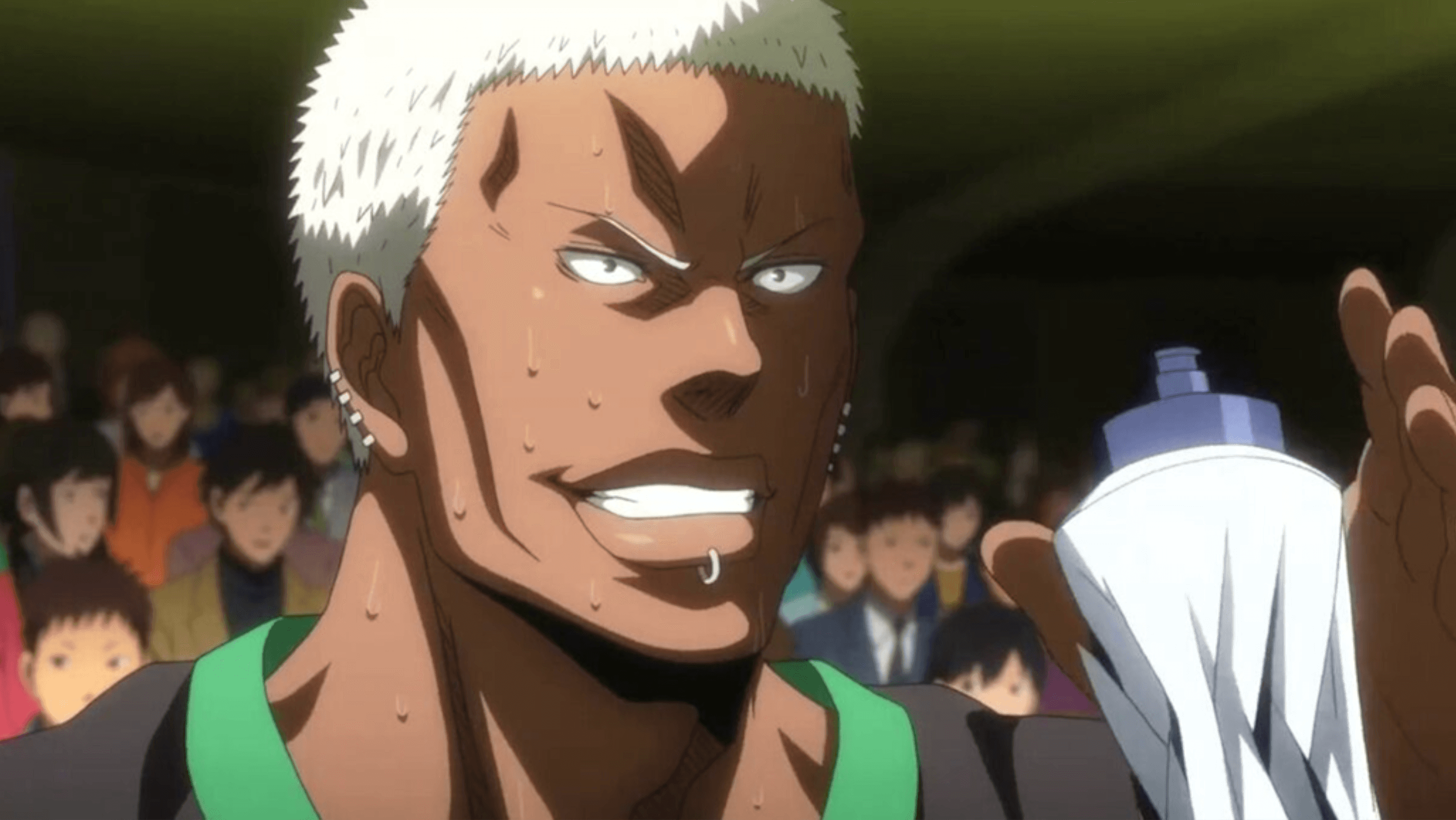

Design, voice, and personality; these are the subcategories that must be considered when creating any character. And with these exact elements we can examine the problematic stereotyping often applied to both overtly and coded Black characters. Take for example the characters of Jason (Kuroko no Basket) and Aran (Haikyuu) in regards to the aforementioned subcategories, and how they reflect on their storylines. Jason – along with all of the other Black/dark skinned characters in the series– is overtly hostile from his introduction, with his antagonism reflected in each of the three categories. Aran on the other hand scales differently, feeling more like a “real”(and Black) character.

Both characters avoided the unfortunately common design fumble of overly lined “sambo lips” (mostly..I still have some shading concerns), which is always greatly appreciated. And their large statures make sense in the context of their sports (basketball and volleyball respectively), rather than simply being a marker of their foreignness. But details like Aran’s palms being a lighter complexion vs Jason’s hands being the same brown from front to back show how care and intentionality in design can make a big difference. Both characters also speak coherently in Japanese rather than the clunkier depictions in other shows; however there is a clear difference in the manner of speech, with Jason’s aggression and cockiness being reflected in his gang-like way of speaking. On the topic of aggression, we come to the third subcategory of character making: personality.

As mentioned before Jason is hostile and aggressive, qualities shared among all the dark skinned characters in the show. As writer Anne Lei wrote in a thesis regarding Kuroko no Basket’s Black characters, “characterizations align with real life anti-black stereotypes such as ‘violent,’ ‘lazy,’ and ‘criminal/delinquent ; … all darker-skinned characters in the series, black and ethnically Japanese alike, also happen to have roles as antagonists. It should be further noted that the black characters of these instances… are not shown to show remorse, nor are redeemed/forgiven by Japanese protagonists as most of the Japanese antagonists are” (Constructing Race in Anime pg. 42). Contrastingly Aran is shown as even-tempered and mature, cooperating and working hard despite his natural talent and stature.

Just as Black people in the real world are diverse and multifaceted, so should the anime characters depicting them.

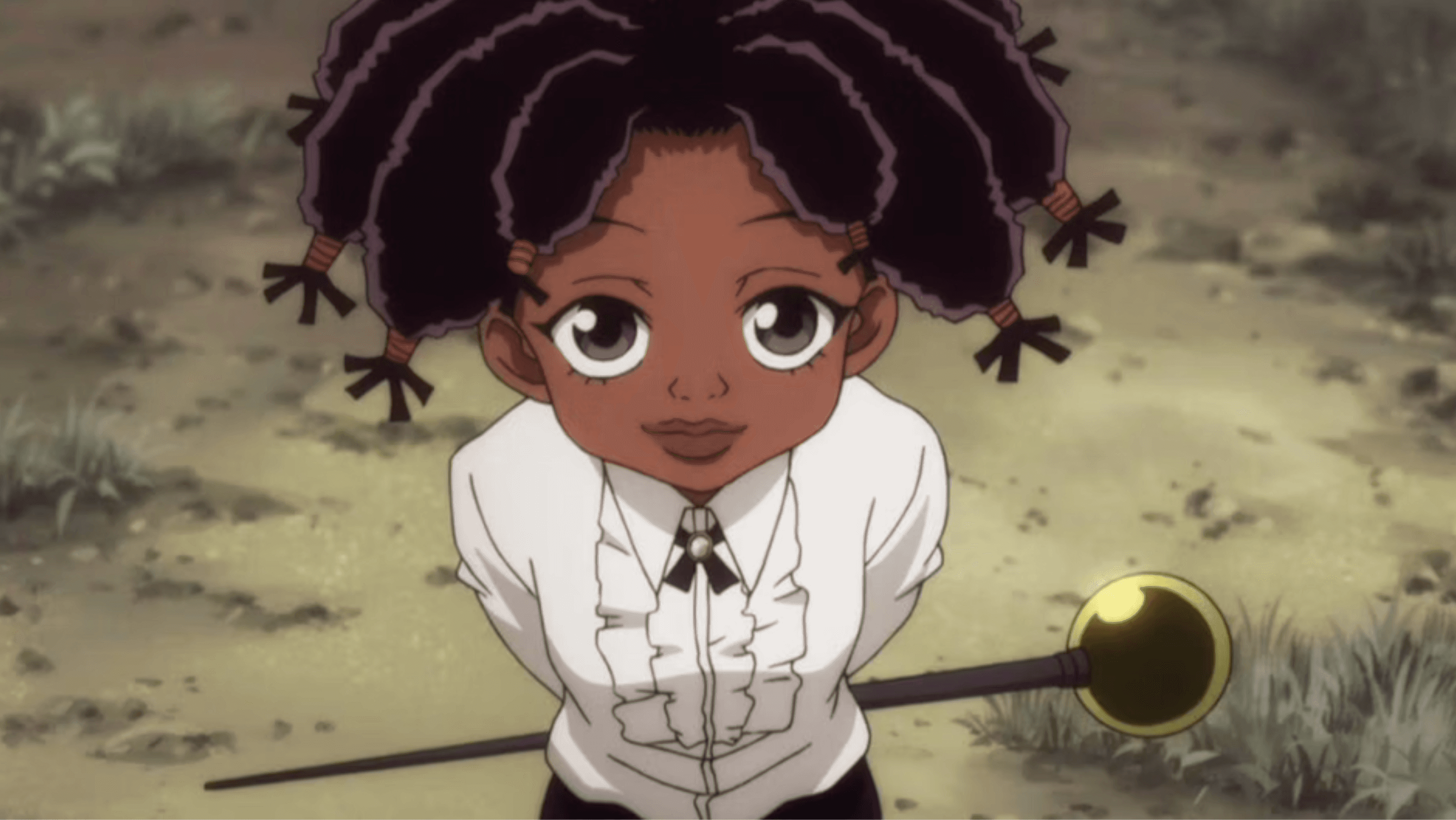

The three development categories are important to basic character making; but, it is especially important that they are taken with even more care when constructing a Black/coded character. While exaggerated features not being the move may be obvious to some at this point, designing a standard a-political “Euro-Anime” phenotype character then dipping them in brown is not the solution for mangakas looking to insert Black characters either. Canary (Hunter x Hunter), Yutaka (Re-Main), and Atsuko (Michiko to Hatchin) fit the aesthetics of their shows – as well as anime overall – while also having beautifully diverse type 4 hairstyles and features that show the care taken in their design. As my fellow writer Tia said in her article about voicing Black characters, rather than play up stereotypical and “eccentric vocalities” because of their skin, the character’s personality should reflect in their voice. Where Yutaka’s voice is unobtrusive and pleasant, highlighting his personality rather than his comparative foreignness, compare this to a character like Zolbe (Saiki K); whose foreignness is not remarked upon by his peers, but instead shown through his oafish broken speech. In fact, Yutaka being “allowed” to be soft and to bake is him being allowed to have a personality that falls outside of stereotypically Black.

Dark skinned characters in anime often suffer a flatter sense of character and shallower motivations due to anti black stereotypes. They are often typecast as being hot-headed, lazy, physically gifted rather than hardworking or smart, and sexual. And even in their antagonism they are “lesser”; take again Jason who is violently evil but subservient only to his white captain, who is also evil but gets to be the “respectable-looking” and cool type. So when Black characters have diverse traits that reflect the diversity of Blackness in the real world, it’s so refreshing and lovely to see.

Aran being shown as the most mature team-mate, Noe (Case Study of Vanitas) being described as the kindhearted naive one of his duo, and Yoruichi (Bleach) being portrayed as upbeat and playful are all examples of good Black characters on the virtue that they exist as independent characters. Instead of representing a concept – whether comedic, antagonistic, or simply Foreign – they are allowed to have their own motivations and personality outside of being Black. And that is what makes a good Black character; having awareness and care in their look rather than exaggerating their features, and allowing them to be an individual character with their own personality, rather than a collection of “otherness” elements based on shallow – and false – assumptions of what it means to be Black. As we continue to see more awareness and sensitivity with other cultural aspects such as how feminism, sexuality, and other topics are handled in modern anime, I hope we can also see a shift in what Black characters are allowed to be.